- Home

- Michael Crichton

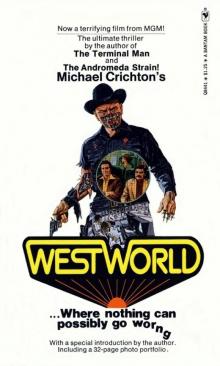

Delos 1 - Westworld

Delos 1 - Westworld Read online

Live out your

fantasies for $1,000

a day at

Westworld—

the ultimate resort!

Murder, violence, wild sexual abandon, any human desire is fulfilled by totally computerized, humanoid robots programed for your pleasure alone . . . Until a small computer casualty spreads like wildfire and one man stands alone against the berserk machines bent on total slaughter!

An adventure in total terror!

GUNPLAY . . . WESTWORLD STYLE!

Blane and Martin’s hotel room. Martin hitches on his gunbelt.

“Say, John, how do I know I’m not going to kill another guest with this thing?”

“Try it. Shoot me.”

Blane is standing at the mirror adjusting his shirt. His back is to Martin. Martin aims, but hesitates.

“Go on, shoot.”

Martin shoots. There is a click; no gunshot. Blane smiles. Martin looks closely at his gun.

“The gun has a sensing device. It won’t fire at anything with a high body temperature. Only something cold, like a machine.”

“They thought of everything.”

WESTWORLD

Where nothing can possibly go

worng

METRO-GOLDWYN-MAYER

Presents

“WESTWORLD”

Starring

RICHARD BENJAMIN

YUL BRYNNER

JAMES BROLIN

Music by

FRED KARLIN

Written and Directed by

MICHAEL CRICHTON

Produced by

PAUL N. LAZARUS III

WESTWORLD

A Bantam Book / published March 1974

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1974 by Michael Crichton.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Bantam Books, Inc.

Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada

Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, Inc. Its trademark. consisting of the words "Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a bantam, is registered in the United States Patent Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, Inc.. 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10019.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FOREWORD

by Saul David

former story editor, MGM

A while ago I had a sort of apartment-office in one of those tall, sleazy-gilt new apartment buildings off Sunset Strip. The daytime life in those buildings has a sort of Sunday on Wall Street dreaminess—it’s quiet, the tenants are invisible, the corridors are empty except for the coming and going of moving men. Yet even at midday the elevators smelled of pot and heavy perfume, and graffiti on the stainless steel doors was often in lipstick or scratched with a key.

Musicians would emerge in the afternoon, blinking, looking sideways at anyone with a briefcase, never getting in or out at the lobby floor. The place came to life late at night though—the corridors pulsed with rock and smoke from balcony barbecues drifted upwards. And now and then the sheriff’s department would kick in a door.

Occasionally there would be a familiar face—a pretty young actress whose divorce was an ongoing conversation piece; a couple of hard-working comics and an immensely tall, absolutely silent young man, blue-eyed and rosy-fair, the very image of a British schoolboy turned junior officer. Absolutely out of place on Sunset Strip and, in those elevators, immense.

He would stare straight ahead, chin tucked a little to avoid grazing the plastic egg-crate overhead grille. When I had a companion and the talk was of books or publishing, I could tell he was listening.

I don’t think we were introduced. We may have been, but if so it didn’t take. Still, I was told who he was and he was not a forgettable sight anyhow—so that over a year later, when I had become a henchman at MGM and was told to attend a meeting to hear Michael Crichton propose a new film project, I instantly said, “Sure, I know him.” In Hollywood you say that, and such are the terrors; no one either believes or disbelieves, not even the know-ee.

As it turned out, he remembered me enough so that the mumbled “Hi” was as convincing as a kiss. And he had a perfectly marvelous project, which you are about to read.

The rest is (to mint one) history—mostly of the kind that razed Byzantium and made cab drivers out of czars. It’s really Michael’s story. But I vividly remember one afternoon—maybe a week before shooting was to commence—when it became my job to summon Michael and his knowing, resilient producer, Paul Lazarus, to a meeting in my office where I was to impart management’s latest. The picture had been canceled twice by then, the budget turned inside out, the principal cast members shuttled like dice and the screenplay revised, denounced, cut, added to and occasionally praised every day for many, many weeks.

That day Michael sat opposite me, Paul on his left. After a while I could only talk to Paul because Michael would say nothing, only stare unwaveringly out of his slump as I went on bravely explaining how it was necessary to add various little scenes all designed to “clarify and explain” sequences which needed neither. And simultaneously to reduce the budget by a considerable amount. I understood the full horror of what I was saying—the mad impossibility of doing what was demanded and the pointlessness of the demands themselves. I loved the project, therefore I was the particular centurion they sent.

Allowing for apologies, it was a long, dry meeting. Paul asked a few questions, nodded, made some notes. Michael just waited until it was all done. Then he got up, said, “I understand,” and left, Paul following.

Later on Paul told me that Michael very nearly quit that night. But he didn’t and the picture was made and we are still friends. Which gives you an idea, I hope.

Michael, I’m sorry the Japanese salesmen sequences were cut from the screenplay. But considering the movie WESTWORLD, I’m glad you didn’t quit that night.

SHOOTING WESTWORLD

The screenplay for Westworld was written in August, 1972, and subsequently offered to the major studios. Every one turned it down, except for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. That immediately presented a problem. MGM had a bad reputation among film-makers; in recent years directors as diverse as Robert Altman, Blake Edwards, Stanley Kubrick, Fred Zinneman and Sam Peckinpah had complained bitterly about their treatment there. There were too many stories of unreasonable pressure, arbitrary script changes, inadequate post-production, and cavalier recutting of the final film.

Nobody who had a choice made a picture at Metro, but then we didn’t have a choice. Dan Melnick, the new head of production at the studio, assured the Westworld producer, Paul Lazarus, and me that we would not be subjected to the usual MGM treatment. In large part, he made good on that promise. We began preproduction in November, 1972.

Preproduction is the time preparatory to shooting when the creative elements are assembled, the script is polished, the sets are built, the locations picked, and the cast hired. It is a busy period for any film, but we had several peculiar problems with Westworld.

The first problem, to be blunt, was the studio. From the outset, the executives in the Thalberg building were divided on the project: some championed it, others loathed it. The result was something like civil war, and no more pleasant than it sounds. There were arguments every few hours; I threatened to quit every three or four days, after episodes of massive depression.

An orderly preproduction was impossible. We didn’t have our cast until forty-eight hours before shooting began. MGM kept demanding script changes right up to the day of shooting. As we approached that final day, conversations took a more and more hysterical tone, in keeping with the old Hollywood traditions. I remember

trying to squelch a casting suggestion by leaning across somebody’s desk and shouting, “I vomit whenever I see that actor.” At other times I would float through meetings, saying, “You’re gonna love it, it’s gonna be wonderful, you’re gonna love it,” and feeling vaguely silly, but that sort of talk seemed to work.

Our second problem was the budget. MGM had agreed to make the film only if it could be done for less than a million dollars. After a month of preparation, we decided it was impossible. Metro reluctantly increased the budget by $250,000, and we continued work. Even at that higher figure, a number of old studio hands told us it couldn’t be done.

A million and a quarter is a lot of money, so perhaps it’s worth explaining why we were feeling so pinched. Of the total budget, roughly $250,000 went for cast salaries. We had forty speaking roles, and several expensive stars.

Of the remaining million dollars, about $400,000 went for salaries of the crew during the six week shooting schedule. We had about eighty people working on cameras, costumes, props, hair, lighting, sound, transportation, and so forth. Most were paid the union minimum, which is nothing anybody gets rich on.

After paying cast and crew salaries, we had $600,000 for everything else in the film: sets, props, special effects, extras, and so on. This still seems like a lot of money, until one figures it out item by item. For example, a Hollywood extra gets about forty dollars a day plus fringe benefits. Even without crowd scenes, you need several extras a day just to keep your locations from looking deserted. Before you know it, you’re spending $50,000 for extras during the course of the film. And the extras need costumes, and horses. It adds up very fast.

Each specific budget category was so thinly financed as to seem impossible. Out of that $600,000, we could give the art director, Herman Blumenthal, only $75,000 for set construction. Anyone who has ever considered building a larger garage or finishing a basement playroom will understand the dimensions of his problem. For that $75,000, Herman had to build twenty sets covering nearly 200,000 square feet. And although he had certain advantages over standard construction requirements, he also had certain special problems. His floors had to be built with such fine tolerances that a camera rolling over them would not wobble or bounce. Many interiors had to be aged. The detail work had to be excellent because minor flaws become glaring when the image is projected on an eighty-foot-wide screen.

Herman is best known for expensive productions such as Cleopatra and Hello, Dolly. He attacked this problem with invention and high energy. He rented construction units which were later sold for use in office buildings. He transformed existing sets. He built units which could be repainted and altered after shooting, then shot again in another context.

In the final film, almost everything was used more than once. We used one medieval stairway three times, in different places. We used a single underground corridor nine times with six light changes, then tore out a false wall and used the same corridor, now widened, as the robot-repair area. We used one hotel room twice, changing furniture and camera angles. In the case of the hovercraft, we built only half the set (which is symmetrical), but “flopped” half the film left to right in the optical printer, so that the final effect was a full hovercraft compartment. Sometimes these maneuvers forced some peculiar cutting patterns, but the average filmgoer probably never notices this.

Our final problem area was technical. For an inexpensive film, we were blithely using a wide range of special-effects techniques: front projection, rear projection, burn-ins, video replay, and blue screen. Gene Polito, the cinematographer, fortunately has a broad technical background from his early days as an engineer; he saved us more than once.

Three problems were especially tricky. One was the robot eyes. I wanted eyes that looked only slightly unreal, not strikingly bizarre. After some experimentation, we settled on eighty percent reflectant mirrored contact lenses, which gave us flexibility to control the “kick” by lighting. They also had the virtue of permitting the actors to see through them.

The second problem was what we called the “gunslinger POV,” the machine view of the world. We reviewed standard special-effects techniques and rejected them all; they were too familiar, and shared a “filmic” quality—no matter how strange, they still looked like photographic images. I didn’t want that.

I knew it was possible to scan images with a computer, and then reconstitute those images in some other form. I didn’t know whether these techniques could be applied to motion picture film, but the idea seemed worth exploring. I also liked the idea that the machine world-view would be literally that—a series of pictures created by computer. Several experts told us that this was impossible. Finally we found a computer-graphics artist, John Whitney, Jr., who said he could do it. Neither he nor anyone else could be sure exactly how it would turn out, but we decided to go ahead and try it

The final technical problem was burning the gunslinger’s face with acid. Nobody had the faintest idea of how that could be done; the script called for the skin of the face to bubble and dissolve. Frank Griffith, the makeup man, began experimenting, but by the time we started shooting we still didn’t know how to make the effect work.

In all our planning, my overriding concern was to avoid a bizarre, science fiction appearance to the film. The story was strange and certainly suggested a strange treatment; I could easily imagine using wide-angle lenses, eccentric compositions, and disorienting cutting patterns. I decided to shoot the film straight, playing against the strangeness instead of emphasizing it

A major consideration here was the script itself. Most of the situations in the film are clichés; they are incidents out of hundreds of old movies. I felt that they should be shot as clichés. This dictated a conventional treatment in the choice of lenses and the staging. There were a couple of peculiar corollaries to that decision. One was the use of arbitrary crane shots which appear throughout the picture—the camera moves up and down for no damned reason except that’s the way old movies were done. Another was the use of slow motion for shootouts because, in the years since Kurosawa, Penn and Peckinpah explored the technique, slow motion has become its own sort of cliché.

Our shooting schedule was so tight that we had no allowances for errors, mistakes, or problems of any sort. We all knew that this was unrealistic, and we hit our first problem on the third day of shooting. I mention it as an example of the sort of trivial thing that can create an unexpected mess.

We were shooting the arrival of Benjamin and Brolin in the underground corridor. They ride a cart past square blue wall lights. However, we found the set was so white, with so much reflected light, that the colored squares washed out and failed to register strongly. We tried all the obvious solutions and none worked; finally we got it right on the day before the set was scheduled to be torn down.

Our luck held for two weeks, then Yul Brynner got shot in the eye with wadding from a blank cartridge. It was a freak accident; we had taken every possible precaution to avoid precisely that, but it happened. Yul’s cornea was scratched. He shrugged off the injury, which was minor enough, but it made it impossible for him to wear his silvered contact lenses. Whenever he tried, tears ran down one cheek, and the injured eye turned bright red from irritation. We had to shift the schedule radically to allow several weeks for his eye to recover.

In many ways, it was lucky that no one else was injured. I am a stickler for actors doing their own stunts; I think audiences can always tell if doubles are used. But there are always unexpected elements in a stunt.

Jim Brolin had recently broken his leg doing stunts, and was leery of further injury. His part required a fearless, effortless quality which he never felt during all his jumps and falls. To his credit, the audience will never suspect his apprehension. On the last day of shooting, he was to be bitten by a rattlesnake in the desert The actual strike was done with reverse photography—the snake was attached to his arm, then pulled off. In the final film, it appears to strike him.

For most sequences, we used

unmilked rattlers, but we milked the rattler that was attached to Jim’s arm. Even the most thorough milking does not remove all the venom, however—a consideration that Brolin appreciated while the snake was having its fangs hooked into his shirt. Under the shirt he wore a leather and cotton pad designed to protect his arm. Suddenly he yelled that he had been bitten. And he had been, by the small teeth on the snake’s lower jaw. Everyone had forgotten about that He had no ill effects, but he did have a good scare.

Dick Benjamin hadn’t done physical roles before. His first stunt required him to be thrown into a breakaway post that would snap on impact He hit the post so hard that half the set came crashing down on him—drapes, lights, rigging, everything. He emerged laughing. (In the final picture, you can see some of the electrical cables lying around his feet)

In the desert, I needed shots of Benjamin riding along a ridge. We picked what seemed to be a suitable ridge, and set up our telephoto cameras about a mile distant, communicating with the actors by radio. The wrangler, Dick Webb, rode along the ridge and reported that it was pretty windy up there. We were surprised; it was pleasant enough down with the cameras. I asked how windy. “Maybe sixty miles an hour,” Webb reported laconically. I asked if the shot could be made; he said yes. Dick got on the radio and said he’d try it. I was watching through binoculars and gulped when Benjamin appeared on the ridge. His clothes flapped like sails in a hurricane.

Many people have noticed that Benjamin isn’t riding very fast on that ridge, as the sequence appears in the final film. That’s the reason: he was trying to gallop along a sheer drop of several hundred feet, with a gale wind blowing.

Yul had been a circus performer in his youth, and he has great physical prowess. He did a number of forward and backward falls without difficulty, including one at the end of the film when he fell flat on his face with a slamming thump so unnerving that the whole set echoed.

Dragon Teeth

Dragon Teeth Jurassic Park

Jurassic Park Micro

Micro The Great Train Robbery

The Great Train Robbery The Andromeda Strain

The Andromeda Strain The Lost World

The Lost World Congo

Congo Travels

Travels Timeline

Timeline Sphere

Sphere Westworld

Westworld Prey

Prey State Of Fear

State Of Fear Next

Next Disclosure

Disclosure Pirate Latitudes

Pirate Latitudes The Terminal Man

The Terminal Man Five Patients

Five Patients Rising Sun

Rising Sun Binary

Binary The Andromeda Evolution

The Andromeda Evolution Airframe

Airframe Easy Go

Easy Go Drug of Choice

Drug of Choice Odds On: A Novel

Odds On: A Novel Scratch One

Scratch One Dealing or The Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues

Dealing or The Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues Venom Business

Venom Business Grave Descend

Grave Descend Gold - Pirate Latitudes

Gold - Pirate Latitudes Binary: A Novel

Binary: A Novel Zero Cool

Zero Cool Delos 1 - Westworld

Delos 1 - Westworld